Foreward

It was the disturbance that woke up the world to Canada’s greatest shame.

You need only say the number: 215.

It’s instantly recognized as the May 2021 discovery of close to that many unmarked graves on the site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia.

The world reacted in horror. How could it not?

Indian residential schools were a systemic, federal government program spanning more than a century (that didn’t officially end until the last federally funded residential school was closed in 1997) aimed at assimilating and — yes, let’s call it what it was — exterminating the Indigenous peoples of what is known now as Canada.

The residential schools were endorsed and operated by multiple Canadian church denominations, most notably the Roman Catholic Church.

A couple of months after the initial discovery of 215 in Kamloops, the number of grave sites there was re-assessed at closer to 200. But consider this: The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, and this is prior to Kamloops, reported more than 4,000 children were confirmed missing or dead while attending residential schools. Many of them are undoubtedly in unmarked grave sites across the country.

After the shocking news of 215 in Kamloops, Canadians felt so much shame and guilt. Some of them for being blissfully ignorant of the existence of residential schools; others for perhaps being aware of them on some level but not enough to really care. The real shame and guilt should be reserved for not knowing or caring that more than 4,000 children were known to have died long before the news broke out of Kamloops. And even since Kamloops, literally hundreds more unmarked graves have been discovered in Canada. And there will be more.

In the spring, summer and fall of 2021, there was this sudden and enormous flood of caring and outpouring of concern. There was a feeling for the urgent need to do something. We took down statues and renamed schools and roads to disassociate ourselves from a bevy of Canadian historical figures, including the first prime minister of Canada, Sir John A. MacDonald, who initiated the residential school program in 1883.

We cancelled many of our July 1 Canada Day festivities in 2021.

We solemnly marked Orange Shirt Day (Sept. 30), put #EveryChildMatters on our orange T-shirts and social media postings; we observed moments of silence before our hockey games; and we threw around all the associated and appropriate slogans and catch phrases — Truth and Reconciliation, Calls To Action — without really knowing what they mean.

Of course, all those things predated 215 in Kamloops and it’s not as if the discovery of unmarked graves at residential schools was an unknown phenomenon before 2021.

One could argue everything we did, as well intentioned as it may have seemed at the time, was geared more to make us feel better about ourselves than to meaningfully help those who suffered through the residential school experience.

Approximately 150,000 children attended the schools. About 90,000 of them received the Common Experience Payment that was part of the federal government’s Indian Residential School Survivor Agreement in 2007. But only about half of those 90,000 are alive today.

If only the suffering ended there. The horrific abuse and trauma inflicted on residential school survivors has been handed down from generation to generation to create pervasive hereditary dysfunction amongst Canada’s First People.

One could also make the case that for all our caring and concern it was just another example of the tokenism, paternalism and colonialism that has plagued the First People since their first contact with the Settler community. That is, we feel terrible about it, but we tend to do so on our terms.

Perhaps the saddest part of all is that it didn’t take too long for post-215 complacency to set in; our caring waned as many moved on to the next righteous cause or concern of the day.

It’s not right.

Hey, I’m about as Johnny (Canuck) Come Lately as anyone on this issue. Growing up, I had a vague awareness of residential schools — I naturally assumed there was nothing particularly good about them — but I never took the time or effort to fully understand the innate evil, staggering levels of abuse and devastating fallout on an entire people.

My friend Gord Downie, the late, great lead singer of The Tragically Hip, took the residential school issue more mainstream in 2016. That’s when Gord, his brother Mike and illustrator Jeff Lemire produced Secret Path, which included an album, a graphic novel and an adapted animated film (that aired on the CBC) to tell the story of Chanie Wenjack.

In Gord’s words: Chanie was a young boy who died on October 22, 1966, walking the railroad tracks, trying to escape from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School to walk home. Chanie’s home was 400 miles away.

I was moved by Secret Path and Gord’s commitment to the cause, but apparently not enough to do anything tangible about it.

So, yeah, I can say from personal experience, it’s not right to do nothing or to let complacency triumph.

Which is why, in the wake of 215 in Kamloops, I decided I needed to further explore the residential school issue in Canada.

If Truth and Reconciliation and Calls to Action are going to be meaningful, I knew I needed to better understand them and that my opportunity to take that journey could perhaps provide a platform for many others like me, hockey fans across Canada and around the world, to do the same.

Since my life’s work has been writing and talking about hockey, I opted to find a hockey context for the residential school issue. It didn’t take me long to find it. Or should I say, find him.

His name is Eugene Arcand. He turns 70 in November. He’s a residential school survivor who not only played hockey there as a child but also as an adult in the Settler community in Saskatchewan. Eugene is a splendid storyteller and has no shortage of great hockey stories. He moves effortlessly in hockey circles. A big Edmonton Oiler fan, his favourite players include Gordie Howe, Mark Messier and Cam Neely, because they played the game the way he liked to play it — rough and tumble; for keeps.

But as a residential school survivor and self-proclaimed damaged goods,

Eugene is first and foremost dedicated to public education. Smart, funny, pointed and a gifted orator, the First Nations advocate tries to heal himself and fellow survivors by talking about their shared trauma. He also speaks to the Settler community to promote greater public understanding (Truth) and charting a path forward (Reconciliation and Calls to Action) for one and all.

I first reached out to Eugene on Feb. 2, 2022, to explain to him why I wanted him to tell his story, in his own words. He told me he would give it some thought but admitted to me in our first telephone conversation that he was reticent to do so.

It was troubling for me, very troubling for me,

Eugene said. I didn’t want to expand my space. I feel safe (at home), doing what I’m doing. I knew that telling my story to you and your audience was going to change my life for a bit, until the explosion of questions that come out (as a result of it) are over. So that was part of my paranoia. The other one was,

Who am I to be sharing this story?

Eugene’s story is but one of thousands from residential school survivors, each of them unique, no one more or less important than another. Eugene’s story is not the story; it’s a story. And Eugene didn’t want to tell his story and have anyone feel like he was doing so out of self-importance or anything other than to help his fellow survivors heal and/or allow the Canadian Settler community to better understand the residential school issue.

Eugene had other concerns, too. He said he’d been burned before in dealings with media who chose sensationalism over honest, responsible storytelling. He also said retelling his story can lead to reliving all his trauma. So, he chooses carefully when and where he puts himself through that, but when he does, he does so full bore,

in the name of healing, public education and understanding.

When Eugene was struggling with this particular decision, he sought the counsel of his Cree Nation elders.

It was reinforced by the old people to me,

Eugene told me. They said to me,

pukuh ka acimoyan,

which means, You have to tell the story.

They also said, Napew awa e tapwat, tapewin.

That means This human being tells the truth.

So, that is why I decided to share our journey together.

By the third week of February, we had an agreement to proceed. I presented to Eugene a pouch of tobacco, as is the custom, and we (virtually, by video) shook hands to make our arrangement official.

In an effort to save time and avoid the potential for re-victimization, Eugene suggested we limit the retelling of some parts of his story that have already been told in other forums. So, he provided me access to those forums, along with permission for the use of his words on TSN platforms.

Much of Eugene’s story here comes from a recorded two-hour speech he gave in Beaumont, Alta., in July of 2021. Some of it also came from a recorded event Eugene spoke at in the wake of the discovery of more unmarked graves at a residential school site at Fort Pelly, Sask., in February of 2022. Two first-person stories by Eugene in the Journal of Sports History (Vol. 46, No. 2, Summer 2019) were also invaluable in providing details and background on Eugene’s life and were used to generate more material from multiple follow-up telephone interviews between Eugene and me.

The final product of all our work together over the better part of these many months will appear here on tsn.ca over a five-day period, beginning today. It’s Eugene’s story, in his words. It’s humbling to have been a small part of it. To which I would only add, it’s the most remarkable and impactful story I’ve ever been associated with in my 40-plus-year media career.

Consider it a gift from Eugene, to help us all better understand real Truth and Reconciliation and perhaps decide on your own personal calls to action. I hope you receive the gift as it is intended.

– Bob McKenzie, Author, TSN Hockey Commentator

I still practice my ways every day,Eugene said.First thing in the morning, I smudge. On March 21, I lit a fire and gave more prayers for what we are doing; to make sure we are doing it right and not hurting anyone. That is always my fear. I’m not in the business of hurting any more. I just want to try to repair the damage in our families and communities.

Here is Eugene’s story but it comes with this advisory: It could be triggering and traumatic for residential school survivors and/or their families. The Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day for anyone experiencing pain or distress as a result of his or her residential school experience. Call 1-800-721-0066 and/or visit the First Nations Health Authority website, fnha.ca.

Part One: Life at Residential School

Tansi, my name is Eugene Arcand. I’m from Muskeg Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan and I am a residential school survivor.

I was born on Nov. 17, 1952, and in many ways, I can’t believe I’m still here walking around on Mother Earth.

What I can tell you is that sports, especially hockey, saved my life at residential school. It was my wife, Lorna, and reconnecting with my First Nations culture that saved my life once I was out of residential school.

Hockey, my wife of 50 years, my heritage — I wouldn’t be here today without them. I give thanks to the Creator.

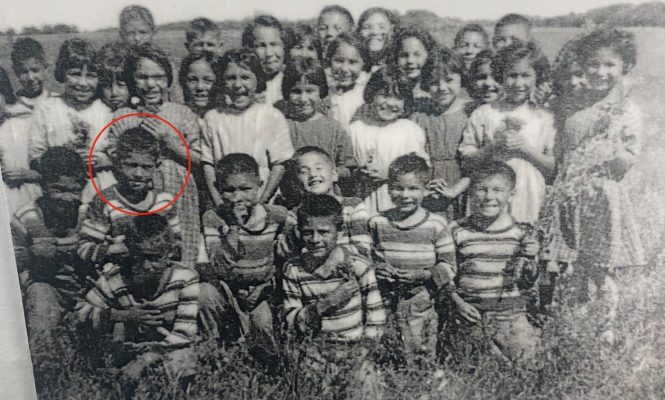

I am here to tell you my story, but I do not come alone. I come here with a picture of 32 children. I’m one of them. It’s a semi-famous picture because it’s been seen all over the world. It travels with me wherever I go and all the children in the picture travel with me, too. Only 9 of the 32 are still alive, but they are all here with us today. Whether you believe that or not, I know it to be true.

I don’t tell my story to make anyone feel sorry for me. I am not looking for pity. I tell my story for public education and understanding. I’m not trying to load any baggage on you. If you feel it’s too heavy, I respect your space. If you think it’s crap, you’re free to stop reading. But if you want to shed a tear, that’s okay, too, because I’ve come to understand that it’s okay to cry. That wasn’t always the case. After going through 11 years of residential school indoctrination, where you got punched or kicked and you were told not to cry, (not crying) became a habit for me.

My Christian name is Eugene. But in late August or early September of 1958, when I was just five years old, I was one of those kids who was picked up and taken away from my home at Muskeg Lake. I was living with my grandparents. And my mother, Harriett. I have never met my father. I understand I am the result of an affair or a one-night stand. I don’t know the details. There was a point in my life where I let that bother me, but now I don’t care at all. And I was in no position ever in my life to question my mother about it because she took such good care of me with what she had.

So, when I was taken off the reserve in 1958, my name was Wesley Arcand. I was transported with a bunch of kids in the back of a three-tonne truck, the kind that they use to haul cattle. We picked up some more kids at Mistawasis First Nation and then off we went to the St. Michael’s (Catholic) Indian Residential School at Duck Lake.

I don’t know how many videos or movies you may have seen, but the stereotype of the (First Nations) child you saw in line to get into the school, well, I was certainly one of them. I had braids. I lined up outside the door of the school, same as the other little kids.

Once I got inside, I distinctly remember the smell. I have come across the smell a few times in my life. It was an institutional stink, that’s what it was. And there were stools there with no back on them, two or three of them. And that’s where we sat, and they shaved our heads. And then they told us, “Take off your clothes.”

We took off our clothes. That’s the first time I ever recall being naked in front of people other than my mother or grandparents. They told us to get into the shower. There were 25 to 30 little boys and we all got into the shower. And on that particular day the showers didn’t work. There was a hose on the floor, which they used to flood the rink. So, they hooked up that hose and they turned it on us.

That was the first time I ever had a shower. It was a horrible experience. It was cold water. They sprayed us. We came out, there were no towels, and we had to drip-dry, just all standing there, crying and hiding ourselves. Can you imagine what it was like? Imagine if it was your children or grandchildren in that shower room? We had entered a totally different world.

The nuns came in and told us to stop crying. I didn’t really understand what they were saying. I spoke my language back then, but I didn’t really speak or understand too much English.

After you drip-dried, you got into line. There was a boy, a tall boy in my school picture, in the back row of the photo. His name was Pat, and he was two kids behind me in line. We had never met. The nun asked me a question, but I didn’t understand it. I said nothing. She asked me a couple of times. Finally, Pat said to me in our Cree language, “What’s your name?” As soon as he said it, he was instantly struck by the nun, right on the side of his head. That nun hit that six-year-old boy so hard he was knocked to the ground. And just because he spoke his language.

I told the nun, My name is Wesley. Wesley Arcand.

She said, You don’t have to use that name anymore. From now on, your name is Eugene. And you won’t have to worry about that because your number is 781.

I didn’t know it at the time but found out later that John Wesley was a famous Protestant leader (in the 1700s), and the Catholics didn’t like that, so that’s why they changed my name to a Christian Catholic name.

Eugene. Eugene Arcand. 781.

So, that was the beginning of an odyssey of indoctrination, with an everyday threat of physical, sexual, psychological, and emotional abuse. That was my life for 11 years. Outside of a month or two in the summer of the first couple of years, I never really returned to live in my community. I don’t recall ever seeing my grandparents again once I went to residential school. I lost my family, as I knew it.

Residential school turned us into animals. Survivor is the term that is used today because we adopted animal instinct behaviour. Up to that point in my life, I had never experienced violence. I had never experienced hunger. I had only experienced love and hugs at home. But from that day forward, that was out the window. Everything from then on was about survival. Only the toughest survived.

On my second day there, I observed violence. Some of the school supervisors were trying to corral one of the big (older) boys. Fifty years later, I got to tell Henry Felix, who was the student (being corralled that day), that he had quite a role to play in my life. I saw that it took three supervisors to take him down. So, on that day I decided, Okay, if that’s how it works here then I’m going to make sure none of these buggers could get at me. I am going to be like Henry while I’m here. I am going to have to be nuts.

That was the moment when violence became part of my life. The sad part is that as my life went on, I enjoyed being a violent person.

So, I began to change. I learned to lie. I can confess today that in the maybe 150 times I went to confession at St. Michael’s I don’t think I told the truth once. That’s a lot of confession, a lot of lying, quite a bit of praying and it really warped me.

I didn’t just learn to lie; I learned how to steal. I learned how to backstab. I learned how to fight. I learned all that to a point where I liked it. And no six-, seven-, eight-, nine-, 10-, 11-year-old kid should like to fight.

But it became a way of life, along with other learned skills — how to take a punch; how to take a kick; all without crying. You also learned that others getting punished or even you lying and backstabbing to get others punished to save your ass was a way of life.

This odyssey had detrimental effects on so many of us. I’m one of the lucky ones — if there is such a thing — to be walking on Mother Earth today and able to share this true experience with you. And it is all true. To this day, I continue to hear all the negativity and skepticism toward what we experienced. Get over it,

they say; they call us liars; say that we were making up stories. Well, I don’t know if you believe it but trust me, these are not the kind of stories you make up.

When you experience childhood trauma like all of us did at residential school — the physical, mental, emotional, and sexual abuse — being taken away from your parents at such a young age is just one small example of the terror we experienced; and the terror we then imposed on one another. The first seven years, as a small or medium boy, was pretty rough. You had to fight your way to the top in order to survive.

Starvation was the order of the day. You may hear, Well, it couldn’t have been that bad. Something good must have come out of those residential schools.

Well, I’m not here to tell you everything about residential schools was bad but I am here to tell you that not a helluva lot of it was good. And the only thing I’ve come out of it with that is worth anything is my life-long friendships; the safety of being with my former schoolmates and other residential school survivors.

Today, being with my fellow survivors is the only place where I truly feel comfortable. It’s the only place I can think straight, other than maybe being on a golf course or watching a hockey game or a ball game.

From the moment I arrived at residential school, my only goal was to get the hell out of there. As a little boy there in the first few days I observed things. I saw some of the big boys getting fed properly, differently. I found later they were members of the soccer team. They were being groomed to play in high school competitions that fall. I saw that the athletes there were getting preferential treatment. I wanted that, too.

I never played sports until I went to residential school. Luckily, the Creator gifted me with skills I did not know I had. I worked on those skills in every sport, and I became good at them. Not because I wanted to be good (at sports) but only because I wanted to get out of there every chance I could, to be treated better than others.

I do remember skating and playing a bit of hockey at Muskeg Lake before I was taken to St. Michael’s. My Uncle Bert scraped out a chunk of ice on Muskeg Lake and I would be out there skating with my cousins, Bruce and Greg Wolf. Those few times I was on that ice really helped when I got into that animal instinct environment at residential school. We were a step ahead of the other kids who had never skated.

At St. Michael’s, whether it was hockey, softball, soccer or whatever, we started in house league. Little boys, medium boys, and big boys — every house league team was made up of those three groups, usually four of each on a team.

It was an adventure just getting the equipment to play. The supervisors would come in with gunnysacks full of skates. Some of them weren’t even in pairs or tied together. Maybe half were. The rest were mismatched. You didn’t actually get given a pair of skates. They’d empty the skates out of the gunnysacks and we’d all dive in to get them. They were mismatched sizes or two lefts and two rights. You’d have to trade to try to get a matching pair. When you were little, after you skated, you had to give the skates back. When you got older, though, you would get to keep your skates.

It was a battle to acquire equipment, too. Shin pads, then hockey pants and all that stuff, every time it was a fight to get what you needed. Until you got to that stage where you were kind of a good player and then they let you keep your equipment. Then you would get all your equipment for that year, and it would be numbered. So, my skates, my shin pads, my pants, they all had 781 on them.

The next battle was to get on the travelling team. It was ruthless trying to make the team. We would hurt one another to increase our chances of making the (traveling) team. It was survival of the fittest. Animal instinct behaviour at a very young age was normalized. We were seven and eight years old when this was happening.

We would play local Settler teams — in Rosthern, Wakaw, Hague. It was engrained into us that the opposing team was an enemy. In hockey, no team came to visit the school. All our games were road games. I didn’t mind that. I just wanted to get the hell out of there. But the Settler teams we were playing against were the enemy.

I held my own. I was a middle-of-the-road player then; maybe more than that. I played like Terry O’Reilly, Cam Neely, and Mark Messier. Rough and ready. Full bore all the time. Those are my guys.

Hockey was an escape for us but some things you can never really escape. As an adult, my wife, Lorna, and I were cruising down the street in Wakaw to visit some people there. Out of nowhere I got triggered by a memory and had to pull the car over to the side of the road. Wakaw is where my friend Leo Knight, who’s in my class picture, was badly injured. It was a cold and snowy Thursday night in Wakaw, and Leo was skating backwards. We were only peewee age, 10 or 11 years old. He stepped in a crack in the ice and fell down only to find out later he had broken his ankle.

We stopped in at the Wakaw hospital on our way home after the game. They gave Leo two aspirin and sent us on our way back to the school. He’s the same age as me and he’s never walked properly again. Outside of those two aspirin and being in the (school) infirmary for a number of weeks, Leo never did receive any real medical attention for a broken ankle. I remember after that Leo’s brother Eddy had to sneak food up to him (in the infirmary) because Leo was no longer (an athlete); he was no longer a priority.

I had to support Leo in the Independent Assessment Process (IAP) in the Indian Residential School Survivor Agreement (IRSSA) because they called Leo a liar. He told his story (of the broken ankle); they didn’t believe him. I went and testified on his behalf; I told them I was there and what happened to Leo. But that incident triggered me in Wakaw that day. I didn’t expect it.

It took me back to the reality of me visiting the supervisor who was in charge that day. His name was Harvey. He’s passed away now. I called Harvey a guardian angel because we did have some guardian angels at school who tried to take good care of us. I would say 75 per cent didn’t care about us at all. And they had their way with us. But over the course of 11 years, 25 per cent of them tried to be our guardian angels and Harvey was one of them.

But I got to ask Harvey, How come you made us get dressed at the school for all our games and tournaments?

All the other kids got to run around the rink between games, out of their equipment, except us. We had to wear our hockey uniforms all day and they stunk. After every game we would go onto the bus and they would feed us sandwiches. They fed us good. That was really the only place they fed us well because they had to showcase us, and they needed us to perform. But after each meal, we would line up and have to go back into the rink and we all had to sit together, still wearing all our equipment.

I asked Harvey, Why would you guys do this to us?

And he said, So you wouldn’t run away.

Little did they know, we knew the preferential treatment we got by being athletes at residential school was not something we would ever risk by running away. But what Harvey told me just chokes me up. It still does. We were little 10- and 11-year-old kids playing against enemies. It’s only been recently I’ve been able to touch base with some of the older Settler gentlemen I competed against then. They used to wonder why we didn’t socialize with them, but we weren’t allowed to.

So, I grew up with sports in residential school. I grew up as an athlete. As damaged as I was, that’s why I can still say sports saved my life. Sports, but especially hockey, saved many of our lives. The Catholics, the clergy, they liked to show off the mission kids. And that whole process of showing off the mission kids, it kept people from asking hard questions (about residential schools). They would say, They must be doing something right, training all these little Indian boys and girls to be good athletes and taking the Indian out of the child.

So, nobody asked questions about what was really going on at those schools.

We were so lucky to be gifted (athletically) because so many of our buddies we went to school with who weren’t athletes got hurt so bad there. They got hurt worse than us because it was a class system. Just look at my report cards; I actually got smarter during hockey or soccer season. I mean, I was a 55 per cent student most of my life. During hockey season, my marks would be in the 70s. As soon as hockey was over, back to the 40s or 50s. How do I reconcile the unfairness of that? I don’t. There are too many of us who had our lives saved by playing sports.

All that said, when you experience the kind of psychological damage we suffered because of a social engineering experiment that went badly wrong as part of Canada’s darkest secret, well, of course when I came out of residential school in 1969, at 17 years old, I was embarrassingly the most dysfunctional person you would ever want to meet.